The Defense Intelligence Agency conducted the first Black Dart exercise in 2002 under a veil of secrecy, and the annual event stayed veiled through 2013. Now run by the Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defense Organization (abbreviated JIAMDO and pronounced “jye-AM-doe), Black Dart’s existence was revealed in 2014, and select media were invited for a day last year “just to let everybody know that the Department of Defense is aware of this problem, we’re concerned about it and that we’re working on it”.

Black Dart 2015 will feature tests of 55 systems brought to Point Mugu at their own expense by an assortment of military units, government agencies, private contractors and academic institutions.

JIAMDO’s $4.2 million budget for the event covers the cost of running the Point Mugu range and providing a small fleet of “surrogate threat” drones. For five hours each day, Gregg’s Black Dart team will fly up to six drones at a time over the range while participants test radars, lasers, missiles, guns and other technologies they think the military might use to detect and kill or neutralize drones of all sizes.

What’s worked

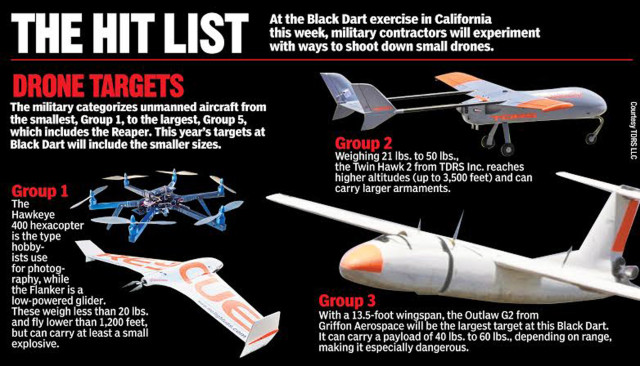

This year the surrogate threats will include three Group 1 drones — a Hawkeye 400 hexacopter, a Flanker and a Scout II — and one Twin Hawk drone from the Group 2 category (21 to 55 lbs., slower than 250 knots, lower than 3,500 feet). Six Group 3 drones, all of them 13.5-foot wingspan Outlaw G2s made by Griffon Aerospace, also will be targets.

One nice feature for contractors: Failure is an option. Black Dart isn’t an official procurement milestone, so companies can test their technologies there knowing that if they don’t work as hoped, there’s no obligation to file a report that might lead the Pentagon or Congress to cut their funding or cancel their program. They can just use the test results the way test results were meant to be used — to find out what works and fix what doesn’t.

“We should have about 1,000 people at Black Dart this year between participants, observers and support,” Gregg said, noting that the departments of Energy and Homeland Security both will send observers. But while Black Dart is no longer secret, the public isn’t invited. “It’s absolutely not an air show,” Gregg said.

Even the media won’t be allowed to see or hear about everything that goes on at Black Dart 2015. Much of what previous exercises came up with in the way of countermeasures also remains classified, said Marine Lt. Col. Kristen Lasica, spokeswoman for the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “We can’t let the enemy know what we’re going to do,” she explained.

That said, some of Black Dart’s declassified successes over the years include:

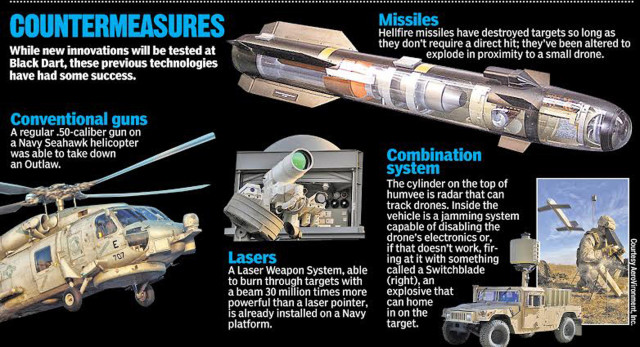

- A Navy MH-60R Seahawk helicopter shot down an Outlaw surrogate threat drone with a .50-caliber gun, proving old-fashioned solutions can work fine against new-fangled threats.

- The USS Ponce, an Afloat Forward Staging Base deployed to the Middle East, today is armed with a 30-kilowatt Laser Weapon System (LaWS) that shot down an Outlaw in a test at Black Dart 2011. The futuristic weapon is also good against slow-moving helicopters and fast-moving patrol boats.

The 30-kilowatt Laser Weapon System was successful at Black Dart 2011.Photo: U.S. Navy

- At Black Dart 2012, an AH-64 Apache attack helicopter killed an Outlaw with an AGM-114 Hellfire anti-tank missile. MQ-1 Predators and MQ-9 Reapers the Air Force flies for itself, and the CIA uses the same basic missile for drone strikes, but the Hellfire at Black Dart was modified with a proximity fuse to detonate in the air next to the target, demonstrating another way to defend against drones.

- Test results at another Black Dart helped Syracuse research and development lab SRC Inc. write software tying together three devices to create a drone counter-measure “system of systems.” SRC connected their AN/TPQ-50 counter-fire radar, designed to detect and track the source of incoming artillery, mortar and rocket fire, to their AN/ULQ-35 CREW Duke electronic warfare system, which jams and locates remote-control devices. Then SRC tied those sensors to a Switchblade, a small, tube-launched drone with sensors that can carry an explosive charge the size of a hand grenade, made by AeroVironment Inc. The result is a weapon that can either jam, take control of, or shoot down a hostile drone.

The latter stands as “one of our greatest success stories from Black Dart,” Gregg said.

It also illustrates one of the major findings of Black Dart over the years: there is no “black dart” — no single weapon — to counter drones. The best defense clearly lies in cobbling together “systems of systems” as SRC did, to detect, identify, track and neutralize hostile drones.

Low, slow and small

Doug Hughes evaded radars, cameras and other detection devices when flew his gyrocopter down the National Mall—despite it being the most restricted public airspace in the nation.Photo: AP

Doing all that is a bear of a problem, especially when the challenge is to spot and stop a small drone. “We’ve gotten better at detecting some of the Group 3 size, the larger UAS that are flying today,” Gregg said, but the limitations of radar and other detection methods make it harder to even see what the Defense Department calls LSS — Low, Slow, Small.

“They’re the same size as birds and other obstacles that are out there,” Gregg said.

Florida mailman Doug Hughes starkly demonstrated the problem on April 15, when he flew a gyrocopter down the National Mall undetected — through perhaps the most restricted public airspace in the nation — and landed on the west lawn of the Capitol with letters to Congress demanding campaign-finance reform.

Hughes evaded “a vast network of radars, cameras and other detection and warning devices,” the commander of the North American Aerospace Defense Command, Adm. William Gortney, told a congressional hearing, because his man-sized gyrocopter “fell below the threshold necessary to differentiate aircraft from weather, terrain, birds and other slow flying objects.”

Group 1 drones are a lot smaller than a gyrocopter, and the difficulty doesn’t stop there. Because small drones “have a very limited range,” they would be launched close to their targets, Gregg said. “So because they’re launched at a very close-in range, even if we can detect and track them right away, there may not be a whole lot of time to make a decision on what to do.”

Especially if an enemy were to launch a swarm of drones — a tactic the US Navy has been developing.

In addition to all that, even if defenders spot a small drone and can track it with enough time to try to knock it out of the sky — a shotgun might suffice in many cases — doing so in a city could risk harming innocent bystanders or damaging property. And what if that LSS UAS flying near the Capitol isn’t controlled by a terrorist but by a kid who just doesn’t know any better than to play with a drone on the Mall?

“It’s a challenge because technology’s not static, it keeps evolving,” Gregg said. “We’re keeping at it, but I don’t think that we’re going to ever probably be able to just stop and say, ‘All right, we’ve got this licked.’ ”

Lasica agreed the threat is a challenge but said progress has been made. Past Black Darts, she said, “have resulted in countless improvements, technologies, tactics, and systems which have refined our ability to operate, detect, track, negate, and neutralize UAS.” The drone threat may be increasing, she added, “But I can say with confidence that our countermeasures are also increasing at a rapid rate, and we’re going to remain vigilant.”

Source: New York Post